David Clarke, the enfant terrible of silversmithing, relishes any opportunity to challenge the conventions of his craft.

London-based silversmith David Clarke is delighted with the outcome of a recent tutorial he led at the Birmingham School of Jewellery. “I had 36 students shouting angrily at each other and there were complaints to the college,” he recollects. “It was great to get them feeling good, confident, alive and passionate about something!”

The artist gets a serious kick out of pushing people’s buttons. A Dutch colleague at the Konstfack University College in Stockholm, where Clarke is associate lecturer, asked him recently if he were the ‘terrorist of silversmithing’. While tickled by the question, Clarke objects to its flippancy. “I’m not just arbitrarily doing this. It is a lot more focused than that.”

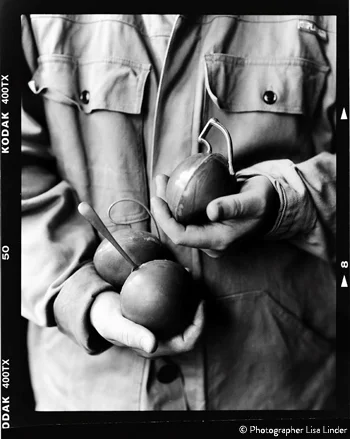

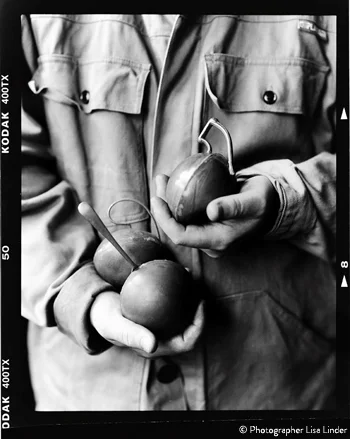

One can see his point. Clarke is known for doing things to silver that make conventional silversmiths flinch in horror. Brouhaha, acquired by the Victoria & Albert Museum in 2007, is indicative of Clarke’s transgressive approach: the ‘reworked teapot’ is part of an ongoing series in which he buys unwanted pieces of silver tableware on eBay and unceremoniously dismembers, alters and bonds them back together.

He uses non-precious metals, such as tin and pewter, seen in his recent series, Unusable Tableware – or, in the case of Brouhaha, highly poisonous, roughly soldered lead. “The more ornate and vulgar, the better. I only bid on pieces that no-one bids on. I want the most unloved and ugliest,” he says.

In earlier pieces, he aimed to render the silver completely unfunctional. “Bringing lead into tableware is absolutely wrong. It is just something you don’t do.” It’s not just notions of public health that are challenged by the silversmith’s work. “Lead is absolutely forbidden in the silversmith workshop because, if you heat it up, it eats through silver like cancer. It is just fantastic.”

Other experiments have seen Clarke render the silver vulnerable by applying a salt solution to an object’s exterior. Salt scars the material’s surface and, if left, will destroy it completely.

“Everything to do with silver gets on my nerves.”

For someone who spent years honing his skills in an industry as laborious as silversmithing, Clarke finds silver profoundly “irritating”, which makes it easy for him to watch it made broken and rendered imperfect.

“Everything to do with silver gets on my nerves. People put on white gloves to handle it because it is deemed so precious. And silversmithing is utterly conservative and so predictable. I find it very, very difficult dealing with that.”

This antagonistic spirit has driven Clarke’s work since 2001, when he decided to funnel it into something positive and turn his back on a commercially successful but unsatisfying career creating architecturally driven, contemporary silver tableware. “I was bored creatively,” he says. “I had become this machine that just produced pieces.”

Since then, Clarke’s evolution has been public and thrilling, with clients and peers unsure what he’ll do next. “It’s the level of perfection in silversmithing that I really moved against – the belief that you should polish every joint until the process becomes invisible,” he says. “There’s something lovely about the knock and dent and life that something has had.”

It’s an ethos which has found its way into Unusable Tableware, where what was once polished becomes raw and all that remains is the mere residue of purpose. Spoons are perforated with holes, rendered too shallow to carry liquid or conjoined with utensils at odds with their own theoretical purpose.

This cheeky reallocation of expectation is echoed in Clarke himself. “I’m not even sure I would call myself a silversmith anymore,” he muses. “But I don’t really care – I am not interested in a box or a name.”

This story first appeared in Vogue Living Mar/April 2011. Click here to download a PDF of the original story. Photographs courtesy of Lisa Linder.