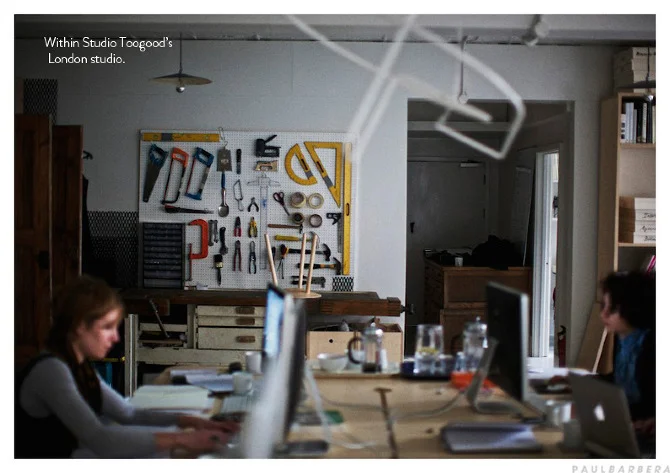

Photographer Paul Barbera makes art from the work environments of artists.

‘‘There is something very romantic about the workspace of a designer or artist. It is obvious that it will be messy,” says Australian photographer Paul Barbera. “It is my craft to find the peace and harmony in the space.”

Barbera has made photographing creative space an art form, posting on his blog Where They Create the workplaces of the people he’s met travelling as a photographer for publications including Vogue Living.

In 2011 he released a book showcasing 34 workspaces taken from a roll call of the cutting edge of fashion, design, art and creative publishing that includes designer Maarten Baas, fashion retailerOpening Ceremony and industrial designer Matali Crasset. The book also features interviews with all the artists by design writer Alexandra Onderwater.

Most studios are exclusive to the book and were shot on a nine-month journey that took Barbera to creative communities in Amsterdam, New York, London, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Bangkok and Warsaw. The evolution of the project confirms Barbera’s belief in “following your bliss”.

“The project has all happened very naturally, but it has brought together all these different aspects of myself: my love of travel and that I get inspired by shooting interiors. I believe that when you follow what you love, you will always find a way to attain the life you want.”

Barbera’s passion for recording creative studios had its genesis more than 20 years ago. “I have been shooting studios from when I was 17, those of friends who were painters and artists. It was innocent; I just felt compelled to document their spaces.” An off-the-cuff discussion with friends about possible analogies between creative space and creative output gave Barbera the impetus to get the images off his hard drive and into the public realm.

“The blog started as something that I did for myself, really, and maybe people found it and maybe they didn’t.” The response was almost instant, with networks of international design bloggers reblogging the images to a growing base of admirers, who were captivated by the intriguing proposition behind the project and the photographs’ essential beauty.

As word of the project spread, increasing numbers of people offered access to their own network of contacts. “Initially I was shooting studios a lot more haphazardly, but in the last two and a half years, the project has given every space and every person I meet a whole new purpose, and my meeting them a point of a focus. Because it is kind of a free project, and everyone is willing to help, they think, ‘Who do I know that you would love to shoot?’ It all becomes a point of communication, a point of exchange.”

The project’s popularity is as much a testament to the enduring mystique of the artist’s studio as it is to the elusive quality of Barbera’s photographs. The images capture the almost mystical transition that occurs when ordinary objects are viewed in the context of a creative workspace.

Tools and paintbrushes seem to wait in anticipation for their owners to return and make use of them. Teetering stacks of paper and sheets strewn across every surface become the romantic detritus of the flurry of creative activity, as opposed to just being evidence of systematic disorganisation. The slapdash use of objects – a dust-covered fax machine serving as a doorstop, a pot plant-cum- paperweight – become inspired creative responses to ordinary problems rather than stopgap solutions.

Barbera asks his subjects to refrain from tidying their workspaces prior to his arrival. Once he arrives, he takes on the role of an observer. There is no styling of the space, or any rearrangement of objects to create the often quirky juxtapositions and odd details that are a consistent feature of the project. The only major intervention Barbera ever makes is to switch off artificial lighting to make use of natural light.

Despite the naturalistic tone of his work, Barbera is under no illusion that his photographs are part of a documentary tradition. The camera frames his unique perspective and the images are arranged to convey a carefully constructed narrative.

‘‘I turn up, I snap and the story gets told in the editing. It is a journey; I try to build it up to make it feel like you have walked in with me, then build the story of where you are. My interiors also have that feeling - that is always what I set out to do. I don’t always get it but it’s what I’m aiming for, a natural state. Photography is voyeurism but it can be engaging as well.”

This story was first published in Vogue Living July/Aug 2011. Click here to download a PDF of the original story.